K1GGI FMT METHODOLOGY

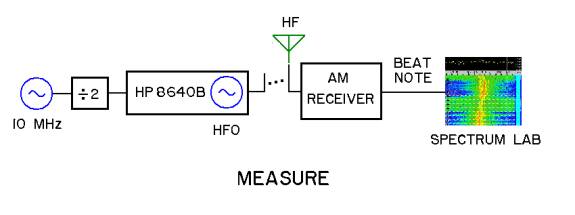

The measurement method is to

heterodyne a precise local oscillator (HFO) with the unknown FMT signal, then

detect and measure the AF beat note with high precision. The implementation

takes advantage of some gear I have on hand.

LOCAL REFERENCE OSCILLATOR

The method starts with

having a high-stability Local Oscillator (LO) as a reference. The best

reference I have is the 10MHz precision crystal oscillator in a HP 8594E

spectrum analyzer. This oscillator is spec’d for 1e-7/year aging and 1e-8 from

0 to 55şC.

HFO SIGNAL GENERATOR

The HP 8640B signal

generator can lock its tuned-cavity oscillator to a reference, such that its

output is a rational multiple of that reference, with 100Hz granularity at

common FMT frequencies. The key property is that the ratio is exact, and

introduces no error.

RECEIVER

The receiver doesn’t have to

be anything special as long as it can tune to the FMT in AM mode and detect the

heterodyne.

BEAT NOTE

The beat note is fed to a

computer sound card and recorded directly as a 44.1kHz wav file for later

analysis with Spectrum Lab software. I use a fairly high resolution fft

(decimate 64, length 32768).

CALCULATION

The 8640B serves as the HFO.

It gets tuned and locked to several hundred Hz below the unknown FMT carrier. A

short wire on the output of the generator is enough for it to be picked up and

produce a beat with the unknown signal in the am receiver. The unknown is then

fx = fHFO + fbeat.

ACCURACY

Results depend on accurately

knowing the HFO and beat frequencies. The HFO frequency is strictly

proportional to the LO frequency; so if the LO is actually 10MHz × k, then fHFO = fset

× k, where fset is what

the 8640 is set to. The prime calibration task is to determine the value of k to high accuracy.

The apparent fbeat

depends on sound card sample rate, which I calibrate using a tone derived from

the accurate LO crystal. The sound-card contribution to beat-note measurement

error ends up being in the sub-millihertz range.

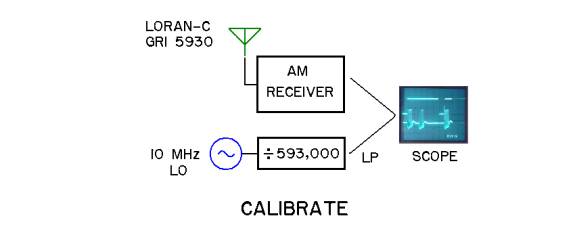

LO REFERENCE CALIBRATION

The LO calibration utilizes

transmissions of the Loran-C navigation system as a reference. Loran

transmissions are pulse-modulated 100kHz carriers with cesium-referenced

timing. Loran-C transmissions were being used as high-accuracy time/frequency

references before GPS was widely deployed.

Nantucket Island, 30 miles

away, is the site of the transmitter for the X secondaries of two Loran-C

chains, GRI 5930 and 9960. The strong stable signal is an excellent off-the-air

reference here.

Complete Loran-disciplined

frequency standards are manufactured and available, but for the purpose of

calibrating an oscillator in the ham shack, I take a hands-on approach using a

general-coverage receiver along with a bit of homebrewing.

The 5930 GRI transmission is

a burst of pulses that repeat with a 59,300 microsecond period. Dividing the

10MHz local oscillator by 593,000 yields a 59,300 microsecond pulse (Local

Pulse, LP) that can be compared with the Loran transmission, as shown here.

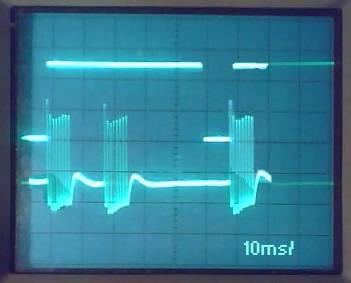

The next photo shows the LP

and the am-detected Loran waveform lined up on an oscilloscope set for a

10ms/div time scale. The scope is triggered on the LP. This scale shows a

complete period of the 5930 GRI, which occupies 5.93 divisions on the

graticule. (This photo has been retouched to overcome shutter and sweepspeed

issues.)

Since Nantucket is

transmitting at two rates, the live scope trace shows the 9960 bursts popping

up all over the place, while the 5930 bursts appear stationary. This photo

happened to capture one 9960 burst. Nantucket is so strong here that it is

difficult to pick out the low-level bursts from the distant master or the other

secondaries, but they are there.

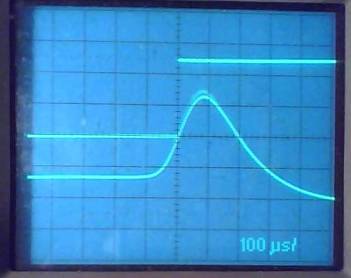

The next photo expands the

timescale to show the leading pulse of the Nantucket 5930-X GRI lined up with

the rising edge of the 59,300µs LP. The traces are positioned so the ‘corner’

of the LP just kisses the slope of the Loran pulse. This makes it easy to see

small changes in the relationship over time.

If the 10MHz LO is as

perfect as the Loran timing reference, there will be no drift seen on the

scope. On this 100µs/div scale, a drift of 20µs (1/5 division) can be detected

by eye. In one hour, 20µs is about 6 ppb (6e-9, .06Hz @ 10MHz), and this is a

‘quick’ way to make a coarse estimate of the LO accuracy. Longer observations

will give better numbers. For example, if the drift is judged to be 100µs ±10µs over 24 hours, that corresponds to 1.16 ±0.12 ppb. If the Loran appears to drift to the right

(coming progressively later), it means the LP is triggering the scope too soon,

which in turn means the LO crystal is running fast.

LO ADJUSTMENT

As described above, a computed

LO correction factor k can be used in

the FMT calculations, and it isn’t necessary for the oscillator itself to be

perfectly accurate, as long as it is stable and its error is known. However,

there is some enjoyment and satisfaction to be had by using the drift

measurements to adjust out the error.

The oscillator module in the

8594 has a multiturn adjustment trimmer, and its spec for initial achievable

accuracy is 22 ppb. Much beyond this, the adjustment gets pretty touchy, due to

end play and hysteresis. With patience and perseverance, I have managed to get

accuracy to within a few ppb.

In my first session trying

this, preparing for the November 2007 ARRL FMT, I found the LO was low by about

400ppb. This is not bad considering that this 8594E is about 10 years old. The

aging would be 4e-8/yr, which compares favorably to the spec of 10e-8/yr.

THE HOMEBREW CONNECTION

The 8640B needs 5MHz to lock

to, so the 10MHz LO needs to be divided by two. The scope needs the 59,300µs

LP, which means dividing the LO by 593,000. The next photo shows how this is

accomplished.

This is a GR 1192B counter,

connected up with a few extra chips on a breadboard sitting at the back. The counter is locked to the LO and a few of

its chips participate by doing some decades of division, while the breadboard

does a final ¸593.

GETTING RESULTS

I check the LO and sample

rate within a few days of the test.

The only skill involved

during the test is to tune the receiver and set the 8640B, then start recording

a wav file. I pick a comfortable beat note during the callup, and make sure to

log the setting and confirm that it is really running below the target, so

things will add up as expected.

Analyzing the file with

Spectrum Lab is done at leisure. The results always have a befuddling amount of

Doppler dispersion. I have been judging the screen images by eye to come up

with a frequency. This part is not an exact science, but for whatever reason,

it has gotten pretty close.